Algonquins of Ontario Land Claim

Presented by Sean Darcy. Article by Maureen McPhee with extracts from presentation by Sean Darcy. Photos by Owen Cooke. April 2019.

On April 17, 2019, RTHS welcomed as its guest speaker Sean Darcy, the Manager, Claims Assessment and Treaty Mechanisms, Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. The subject of Mr. Darcy’s presentation was “The Algonquins of Ontario Land Claim and the Claim Assessment Process.”

The presentation began with an introduction on the 10 communities that comprise the Algonquins of Ontario, who are currently negotiating a land claim agreement with the Governments of Canada and Ontario. Once a final agreement is reached by negotiators, over 8,700 Algonquins in these communities will be eligible to vote to accept or reject the proposed settlement. One of the ten communities is Golden Lake which did receive reserve land, despite the fact that none of the Algonquins ever signed a treaty surrendering aboriginal rights to their traditional lands.

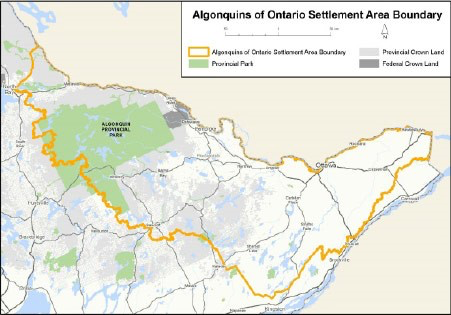

Mr. Darcy’s presentation included a map illustrating the large land claim area in Eastern Ontario that is the subject of negotiation. The area includes most of Algonquin Park and all of the former Rideau Township.

Mr. Darcy outlined the history of Algonquin use and occupancy of the claim area from the point of first contact with Champlain in the early 17th century. From the mid to end of the 1600s, warfare with the Iroquois caused the dispersal of the Algonquins from their traditional areas; however, when the Iroquois left, the Algonquins moved back in. The Algonquins established relations with the British, and under the Treaty of Swegatchy of 1760, they agreed to remain neutral. In 1857, a group of Algonquins who frequented the Golden Lake area for some 50 years petitioned the Crown for lands, and in 1864, Indian Affairs was given authority to purchase lands.

A preliminary draft agreement-in-principle was concluded among the Algonquins of Ontario, Canada and the Province of Ontario in 2012. Negotiations are continuing towards a final agreement, which would be constitutionally protected as a treaty. Key elements of the agreement-in-principle included $300 million dollars for the Algonquins, transfer to them of not less than 117,500 acres of provincial Crown lands, and approaches to addressing Algonquin harvesting rights, forestry, parks and protected areas, culture and heritage, and how eligibility of individuals for claim benefits will be determined. Interests of others in relation to lands transferred to the Algonquins are to be protected and Algonquin Park will remain a park for the appropriate use and enjoyment of all. Key principles that the Algonquins wish to see reflected in a final settlement include reconciliation, clarification and constitutional protection of Algonquin rights, certainty of land title for all, expanded economic activity, cultural renaissance, and mutual respect for all peoples.

Mr. Darcy clarified that the Algonquins of Ontario claim ends at the Quebec border and a final treaty will not deal with the rights of the Quebec Algonquins, who have not submitted a claim in the Ottawa Valley. The signing of a treaty with the Algonquins of Ontario will not prejudice the rights of other aboriginal groups who are able to substantiate a claim in the same area that an Ontario Algonquins treaty would cover.

The Algonquins of Ontario claim is what is known as a Special Claim, as it does not fall within the parameters of existing land claims policies. The claim is similar to what is referred to as a Comprehensive Claim, in that it pertains to the assertion of unextinguished aboriginal rights and title; however, given that the claim area overlaps with regions used by other aboriginal groups who did sign historic treaties, the Algonquins could not meet the criterion that their use and occupation of the territory was largely to the exclusion of other organized aboriginal societies. In 1992, the federal Department of Indian Affairs developed guidelines for the assessment of such special claims.

Assessment and ultimate acceptance of a special claim for negotiation requires very rigorous application of tests established in case law. Mr. Darcy reviewed major Supreme Court of Canada decisions that resulted in the evolution of the law.

The Baker Lake ruling of 1979 established the following tests for assessing claims to continuing aboriginal title:

- that the plaintiffs and their ancestors were members of an organized society; ·

- that the society occupied the territory over which they assert Aboriginal title;

- that the occupation was to the exclusion of other organized societies; and

- that the occupation was an established fact at the time of assertion of sovereignty by Europeans

The Supreme Court’s 1996 decision in the Adams and Cote case stated that an aboriginal harvesting right could be confirmed without continuous occupation of a territory by the aboriginal group, if the activity was integral to the group’s distinctive culture.

The Delgamuukw decision of 1997 established for the first time that aboriginal title is a right to land akin to ownership, whereas more broadly applicable aboriginal rights relate to access and use of land as opposed to its ownership. To prove aboriginal title, a group must establish that it exclusively occupied a claimed territory at the time of European sovereignty and has maintained connection with the territory to the present.

The Claims Assessment and Treaty Mechanisms Directorate of what is now Indigenous Affairs reviews claims submissions from Aboriginal groups, ensures that all facts relating to the claim are thoroughly researched, prepares an assessment report for review by the Department of Justice and on the basis of its legal advice, recommends to senior departmental management and the Minister whether the claim should be accepted and negotiated.

In reviewing a claim, Mr. Darcy said that his directorate looks for evidence of an historic aboriginal collectivity that was present in or using the claimed land at the time of contact with Europeans. Consideration is also given to current use and occupancy. In response to a question from the audience as to whether blood quantum is considered, Mr. Darcy said what is being assessed when a claim is reviewed is historical land use by a collectivity, not by individuals. An individual’s background is only considered at a later date when a determination is made on who the beneficiaries of a signed modern treaty agreement are.

Mr. Darcy explained the detailed evidence and extensive historical documentation that an Aboriginal group has to submit to have their claim considered for acceptance. The Claims Assessment and Treaty Mechanisms Directorate must ensure that all facts regarding the claim are thoroughly researched and assembled for review by the Department of Justice. The Directorate looks at evidence beyond what the aboriginal group submits and then recommends either acceptance or rejection of the claim. If the claim is accepted, approval of a negotiation mandate is sought from the federal Cabinet. Facts matter, as very pointed questions are received from Cabinet Ministers. Given that the results of the Directorate’s work affect aboriginal peoples’ rights and identity, it is very difficult when it is necessary to inform a group that its claim has been rejected. How historical records are used in the assessment process has a real impact upon peoples’ lives.

In concluding his presentation, Mr. Darcy said that the greatest success of his directorate is the cooperative work they do with aboriginal groups to establish an unbiased fact base for a claim. This assists the parties in reaching a better understanding of the facts, as well as each other’s position regarding interpretation of those facts. History is relevant in the work the directorate carries out, as it impacts the lives of aboriginal individuals and all Canadians. Mr. Darcy enjoys his work in that he gets paid to read historical documents and can contribute to recreating the fabric of Canadian society.

Mr. Darcy’s presentation generated a great deal of interest, as reflected by the number of questions from the audience. In responding, he clarified that a claims settlement with the Algonquins of Ontario will not negate the rights of Quebec Algonquins in Ontario and vice versa, should the Quebec Algonquins negotiate their own agreement. He said the Quebec groups are talking among themselves in relation to any future submission of a claim.

A question was raised as to whether the claim area will be restricted by the fact that much of the land has come to have other uses. The response was that while the claim area will not be limited, there will be no expropriation of land owned by others. Thus, there will be limits on where Algonquins treaty rights may be exercised within the claim area. The Algonquins’ loss of use of land will be considered in determining the nature of the benefits in the final settlement. There will be a financial cost to Canadians, and other aspects of the settlement will include surplus Crown properties, economic development opportunities, and perhaps a cultural building in downtown Ottawa. The purpose is to put the beneficiaries on an equal footing with other Canadians. They need an income base and economic development to allow families to support themselves and ensure the future of their children.

A questioner noted that the powers of the government and the Aboriginal negotiators seem to be unequal and asked what inspires Canada to move forward. In response, Mr. Darcy said that court cases have made clear that aboriginal rights recognized under section 35 of the Constitution must be dealt with and any infringement must be justified.