Pioneer Settlement in Upper Canada

Text material adapted from the Tweedsmuir History of Kars, Vol. 3; published by the Kars Women's Institute; Courtesy of the Rideau Branch, City of Ottawa Archives

The first settler in the area of what would become Wellington and later Kars in North Gower township was Richard Garlick, who came in 1821 with a number of loggers and their families, most of whom were United Empire Loyalists. He acquired Lots 30, 31, 32 and 33, Concession 1, North Gower Township, as well as Lot 24. After he had established lumbering operations, he brought his family in 1823.

The first settler of Osgoode Township was Archibald McDonald, a Glengarry Highlander, who drew one thousand acres of land in 1826 for his services.

The settlement of the two townships occurred almost about the same time and for the same reasons, although the settlers knew nothing of the presence of each other for many years. This was because of the difference in the way that the timber was marketed. The wood from Osgoode Township was sent down the Castor River, thence via the Nation River, on to the St. Lawrence, and probably on to the United States. Timber from North Gower Township was sent down Stevens Creek and along the Rideau River to Ottawa, thence to Montreal and Quebec City.

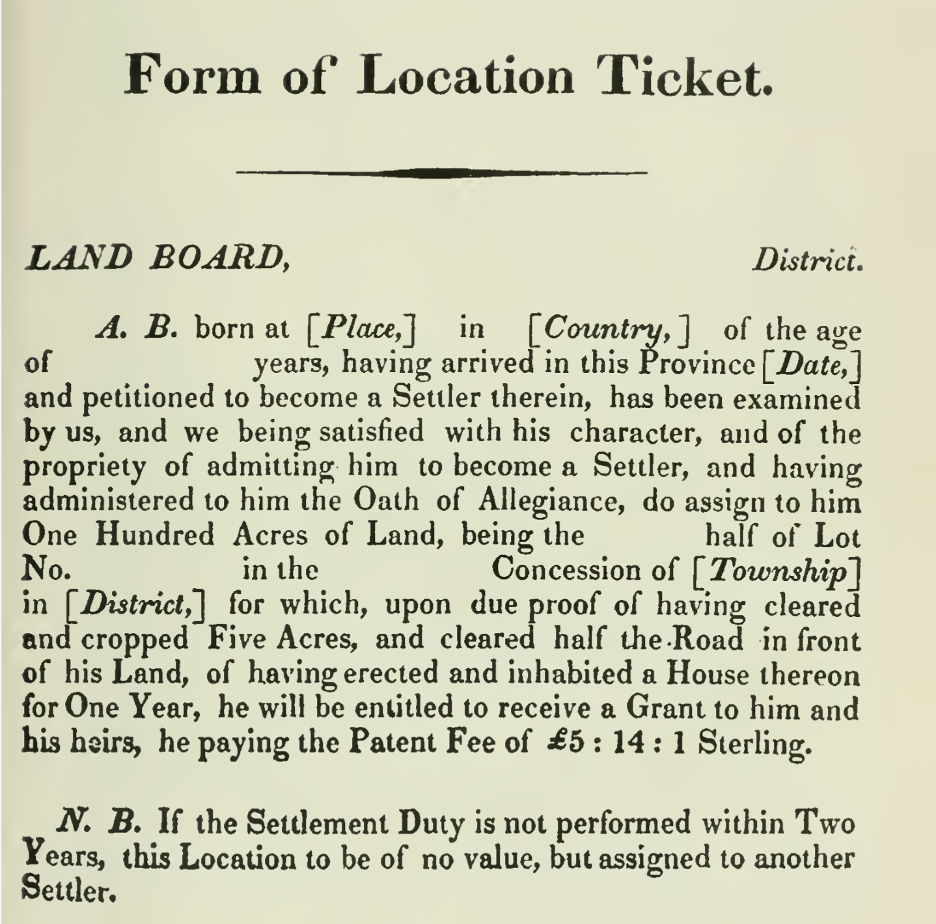

The United Empire Loyalists drew their land at Prescott. A contemporary picture shows settlers choosing land from slips of paper in a hat. If a person disliked the place of his location ticket, he could sell it and go where he chose. The image below is similar to the actual form of the location tickets for the United Empire Loyalists.

Similarly, if a settler found any signs of habitation or clearing on his location, he had to go to another place. Hence. squatters and their rights were recognized early.

In his book "Sketches of Upper Canada" published in 1825, John Howison presented the following advice to settlers.

"The chief objects to be considered in making a selection of a grant, are the goodness of the land, its dryness, the existence of spring of running water upon it, its vicinity to a road, a navigable river, a mill, a running stream, a market, and an extensive and increasing neighbourhood."

"The emigrant's first object then is to get a house built. If his lot lies in a settlement, his neighbours will assist him in doing this without being paid; but if far back in the woods, he must hire people to work for him. The usual dimensions of a house are eighteen feet by sixteen. The roof is covered with bark or shingles, and the floor with rough planks, the interstices between the logs that compose the walls being filled up with pieces of wood and clay. Stones are used for the back of the fireplace. The whole cost of a habitation of this kind will exceed £12, supposing the labourers have been paid for erecting it. But, as almost every person can have much of the work done gratis, the expense will not perhaps amount to more than £5 or £6."

"Flour and pork are the only articles of subsistence which can be conveniently transported into to the woods. Barrels of flour weigh 186 pounds and cost £1/10/0d•, while a barrel of pork weighs 200 pounds and cost £5.

The clearing of land overgrown with timber is an operation so tedious and laborious that different plans have been devised for abridging it, and for obtaining crop from the ground before it is completed. The easiest and most economical system is that named 'girdling'. The land is first cleared of brushwood and small timber, and then a ring of bark is cut from the lower part of the tree. If this is done in the autumn, the trees will be dead and destitute of foliage the ensuing spring, at which time the land is sown without receiving any culture whatever, except a little harrowing. This plan evidently possesses no advantage except that of enabling the settler to supply his immediate wants at the expense of comparatively little time and labour. The crops are of course scanty and of inferior quality. The dead trees must be cut down and removed at last, and, being liable to fall during the high winds, the lives of both labourers and of cattle are endangered.

After the trees have been felled, the most suitable kinds are split into rails for fences, usually the cedar, and the remainder being cut into logs twelve feet long, are hauled together into large piles and burnt. The immediate removal of the roots of the trees is impracticable a nd they are therefore always allowed to fall into decay, to which state they are generally reduced in the space of eight or nine years. Pine stumps however seem scarcely susceptible of decomposition, as they frequently show no symptoms of it after half a century has elapsed.' Settlers often ruined stands of pine in this way, through ignorance.

Potash was one of the first products that the settler could sell. The wood ashes were collected in a covered hollow stump, or an old barrel, which was set upon stones, with a tin under it to collect the lye. Water was poured over this container and as it seeped through, it emerged as lye into the tin beneath. The residue salts were compressed into cakes and sold as potash. This was used for bleaching purposes in such places as the cotton factories in England. The lye was cooked along with bits of rendered (melted and clarified) fat to make homemade soap. This soap was a soft soap, brown in colour. A variation in the soap recipe produced a hard soap.

"In Upper Canada, grain is always put under cover, instead of being made into stacks; and therefore the farmer must build a barn, which at first is usually formed into logs, in the same way as a dwelling house; however, it does not cost as much, no inside work being necessary. If he becomes wealthier, and is more at leisure, the settler may erect a frame barn, so called because it is constructed of joiner work and covered with boards. Such buildings are commonly made fifty feet long and forty feet wide and cost about £60.

When a farmer is able to raise a larger quantity of produce than is required for the support of his family, there are several ways in which he may dispose of the surplus. In many new settlements the influx of emigrants is so great as to produce a demand for grain more than equal to the supply."

A settler would use a grain cradle, such as the photo below, to harvest grain. A cradle was a sickle with fingers on it for bunching the grain.

"But should there be no demand of this sort, he may carry his produce to the merchant. They will give him in exchange, broadcloth, implements of husbandry, groceries, and every sort of article that is necessary for the support of his family, and perhaps even money at particular times of the year. He will likewise often have it in his power to barter wheat for livestock of different kinds and can hardly fail to increase his means, although without a regular market for his surplus produce, if he becomes initiated into the system of traffic prevalent in the country.

As there is no grass in the woods, and as the new settler cannot raise fodder for his cattle immediately, he is obliged to buy either hay or straw or pumpkins to feed them, or to cut down trees for them to browse upon. Oxen and young cows thrive well enough on the tender shoots of the birch and maple, but sheep must have hay or turnips and ought to be secured from the wolves every night.

Money is so difficult to procure, that almost all farmers to pay those they hire with grain of some kind, which, being unsaleable, those who receive it are obliged to barter it away with loss, for anything else they may require. He who has a little money at command in Upper Canada, possesses many advantages. He will get work done at a cheaper rate than other people who have none, and in making purchases will often obtain a large discount from the seller."