The Story of the Home Children ~ Pt. 2

Presented by Coral Lindsay, Georgie Tupper, Barbara Ann (Hannaford) Smith, Joan (Taylor) Melancon, Barbara Dillon, Ruth (Irvine) Shurtliff, David Hayes, and Bill Buchanan. May, 2011.

Article by Lucy Martin

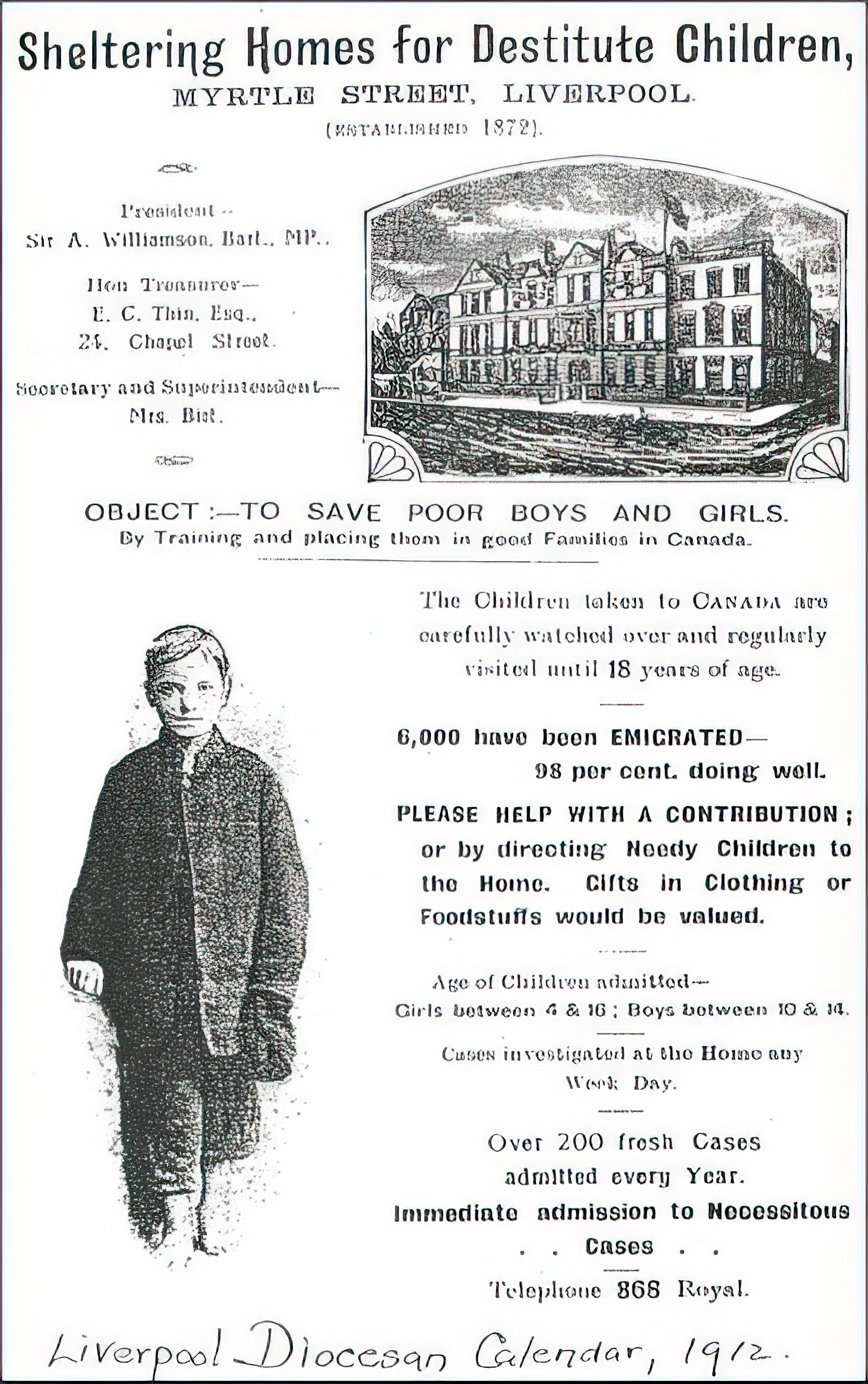

2010 was declared “Year of the British Home Child in Canada”. From 1869 to the late 1930’s over 100,000 such children, typically between the ages of 4 and 15, were shipped away to work in Canada. Many were orphans, some came from families who were unable to feed them, and some came for various other reasons.

To help understand this national and family heritage, RTHS presented an evening of heart-felt personal remembrances from local residents with Home Child connections. The community hall in Pierce’s Corners was filled with just over 50 in attendance along with relevant displays brought by the speakers and Archives volunteer Shirley Adams.

At the meeting, Georgie Tupper explained how every year the Rideau Branch of the City Archives picks a topic for further research and displays. The 2011 focus is on Home Children, the large majority of whom settled in Ontario. Using census records for this area, Tupper found 60 probable Home Children in 1901, a number that rose to 150 by 1911.

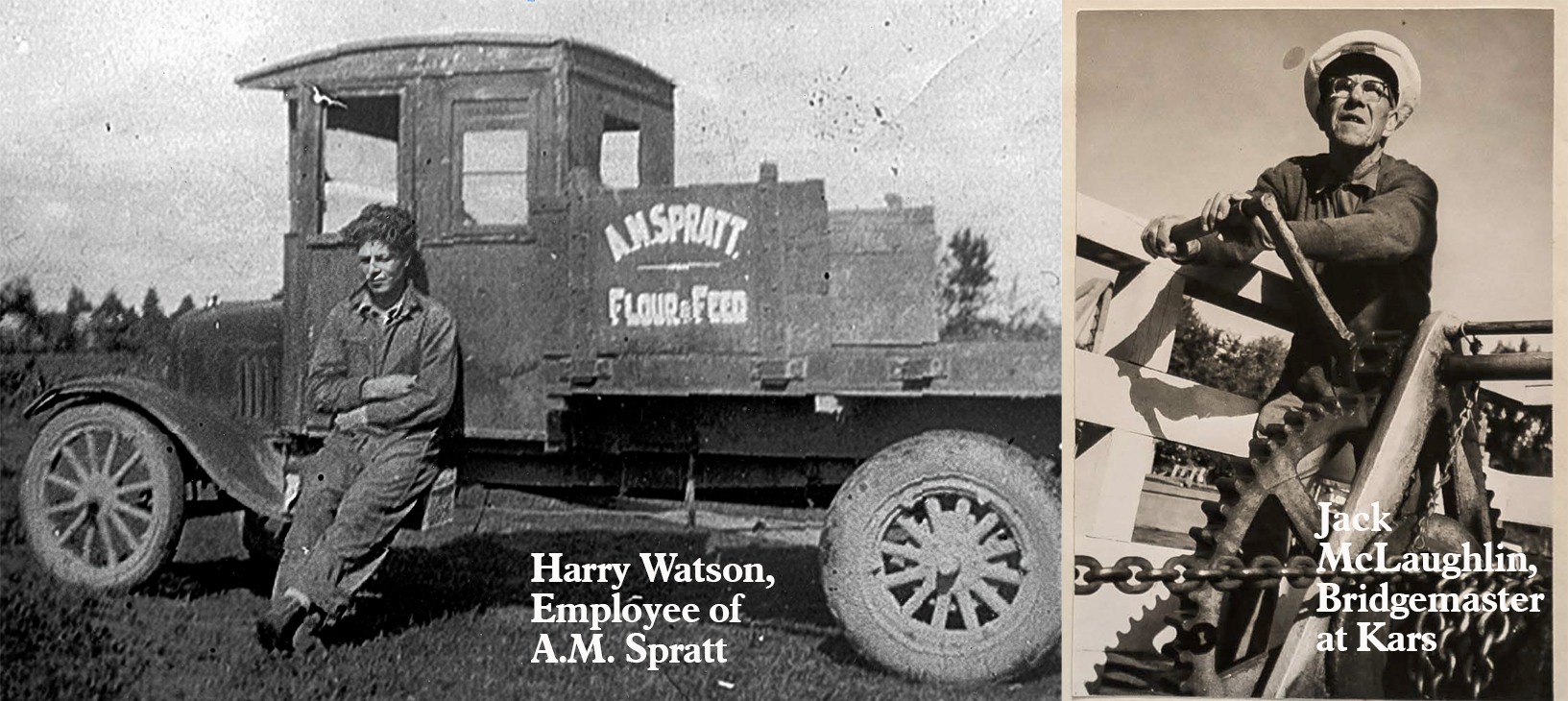

One of Manotick’s founding families, the Dickinsons, hosted a Home Child, Sarah Devlin. Home Child Jack McLaughlin became a bridge master in Kars, while Harry Watson went on to own Watson’s Mill. North Gower’s Recreation Centre is named in recognition of the many contributions made by Home Child Alfred Taylor (more on Taylor later in this article).

Space does not permit doing full justice to the stories shared that night. What follows are summaries of lives that encompassed heartache and triumph over adversity.

Barbara Ann (Hannaford) Smith spoke about being a 6th generation Dillon on her maternal side, but only knowing her paternal grandparents had come from England and Scotland and seemingly had no relatives. She did not discover both had been Home Children until after their deaths.

Smith’s grandmother, Margaret Strang Watters Penman, was the eldest of 6 and endured an impoverished home with a neglectful father. After being in and out of the poor house, Margaret and four siblings were removed from their mother’s custody and ended up separated in Canada after arriving as Home Children.

Smith eventually managed to trace her grandmother’s siblings and learned their stories from descendents of her newly-discovered relatives. Smith was left deeply impressed by her Grandmother’s life-long fortitude and natural kindness in the face of such great personal hardship.

Joan (Taylor) Melancon spoke about her father, Alfred Taylor. He became a pillar of the North Gower Community, much honored for a life that included a meritorious military career along with strong support for sports and community volunteerism. Taylor was also a Home Child.

He began life in a happy, secure family in England, but ended up shuttling among relatives after his mother died of cancer and his father abandoned their three sons. The two oldest brothers ended up in a dismal work house. Taylor was eventually sent to Canada just prior to his 15th birthday as a farm worker. Some of his placements were good. Others were bad.

During the dirty thirties when times were hard and jobs were scarce, Taylor ended up in North Gower, where he found work and fell hard for a beautiful teacher, Madeline Craig, daughter of a well-established family, headed by long-time town reeve, Howard Craig. The two fell in love, married and went on to enjoy 50 years of happiness, family and community service before Madeline’s death.

Taylor told his children he tried to do something good and productive each and every day of his life, that that he felt, for a boy who came to Canada “with nothing”, he made a wonderful life.

Barbara Dillon’s father, George Ferrar, was born in 1889, the youngest of five in Scotland. He was fully orphaned by age 5. His older siblings could not sustain the remaining family on their meager wages. So George and one sister were signed over to an orphanage called Quarrier’s, a noteworthy organization that housed children in home-like cottages with a mother & father figure for each. Pressing need forced Quarrier’s to make room for more orphans by shipping some to Canada. Although initially deemed too undernourished and frail for the journey, one year later, in 1896, George and his sister Jenny were sent abroad.

George had to work hard but was well treated on the farm of John McIntire, on Donnelly Drive, near Kemptville. Jenny was sent to a Moffit farm in the Winchester area. Barbara says her Dad “was one of the lucky ones”. He finished grade 8 and married Alice Crawford in 1917, where he and his wife continued to work on the farm. After Mcintire died in 1941, George learned he had been adopted and would inherit the farm.

Dillon recounted her father’s return trip to Scotland in 1949 where he was warmly welcomed with open arms as a member of Quarrier’s Village. (1937 had been the last time orphans were sent away from Quarrier’s. After that they were kept in Scotland and taught trades.)

Brabara Dillon returned to Scotland herself where she enjoyed a number of tours that explored her family’s history and the role of Quarrier’s in the lives of so many. She recounts what she learned and experienced first hand left her most grateful for the humanitarian work of Quarrier’s.

Ruth (Irvine) Shurtliff spoke about her father, Henry Irvine. He was born in Glasgow in 1902. The youngest of 5, all orphaned when both parents were felled by disease, several years apart. By age 8, with no place else to go, he and his siblings ended up in Quarrier’s Village. After some years there, Henry came to Canada in 1915 at age 12. He was placed with a childless couple, Robert and Leticia Pierce, who were described as good and kind. They left him the farm when they died. (The meeting place, Pierce’s Corners Hall was the end of their farm and was where Ruth grew up.)

In 1928, Henry married Myrtle Goth and raised a large, close family. He sold the farm and moved to Manotick in 1957. Shurtliff has been back to visit Quarrier’s in Scotland twice (in 1997 and 2009) traveling with fellow home-child descendant Barbara Dillion.

David Hayes spoke about his father, Samuel Hayes, a home child born in 1893 in Liverpool, England. In 1907 Samuel and one brother arrived in Canada in a voyage that exposed them to deep cold, requiring some children to be hospitalized on arrival.

The brothers were separated in Canada. One sister arrived a year later, and was reportedly well-treated and adopted. Samuel was mistreated at a farm in Almonte and ran away. He ended up on a McDermont farm in Almonte, where he received good care.

In 1914, at age 16, he enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary force. and served in Europe. He served abroad again in WW II with the Veteran Guards of Canada. He married in 1916, and was surprised to discover he and his wife had both been born in the same house, a year apart.

Bill Buchanan spoke about his paternal grandmother. She was born in either 1880 or 1883. Her father, James Reed, was killed in a construction accident, leaving at least 4 children to care for. His widow tried to carry on but could not manage the financial burden alone. Under the auspices of the Quarrier’s Society two siblings were sent from Glasgow in 1886 arriving in Quebec.

Buchanan’s grandmother came to live with Isaac and Elizabeth Pratt, just south of Drummond’s on River Road. By all accounts she was treated well, she was sent to school. She either came as a 3 year old or a 6 year old. She is listed in the 1901 census as the adopted daughter of the Pratts, age 18. Buchanan joked she was likely older.

She worked hard all her life, though that was normal. She was never formally adopted, but she was always treated well and remained devoted to the Pratts for all her days.

Separated from her brother John Reed on arrival in Canada, his story is less well known. They had very little contact until John came to find her 60 years later in Manotick, for a visit. Buchanan thinks his grandmother had a very good life, before passing on at 89 (or 92!). He looks forward to learning more about the Quarrier’s Society.

We thank the speakers for sharing their personal memories. It certainly expanded our understanding of what Home Children went through and contributed to Canada.