The Irish Experience in the Ottawa Valley

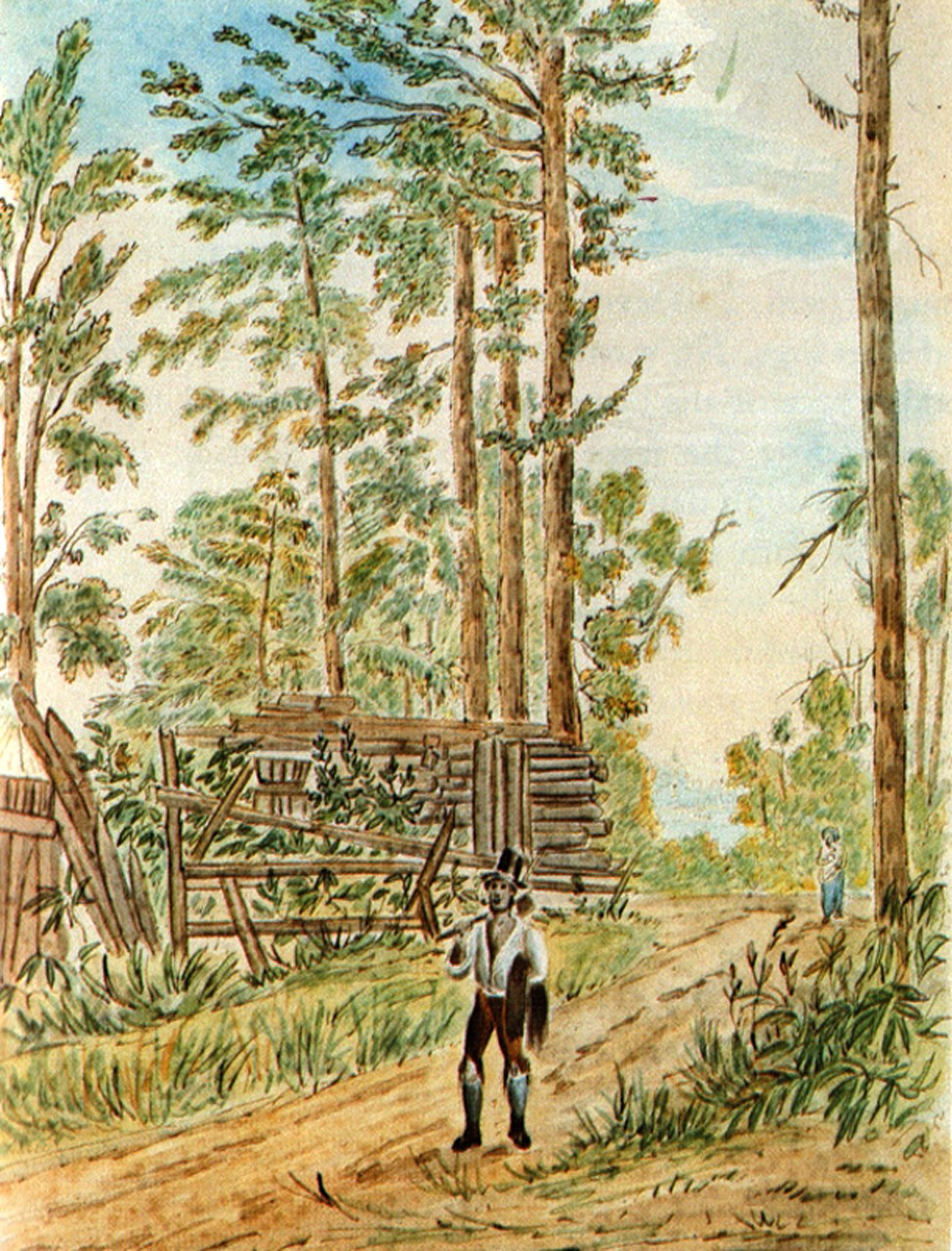

According to author Peter Currie, people are starved, he says, to know about “us”. The Ottawa Valley is unique, as illustrated by its log barns not found in other parts of Ontario, and its unique accents. It’s a single geographic and cultural unity on both sides of the Ottawa River. According to Terry, we, “the Ottawa Valley”, are more famous in Ireland than we realize ourselves.

In the day of Julius Caesar, the Irish were cattle herdsmen, living on small holdings, but were already known as brilliant musicians. Irish musicians were brought as slaves to play in Rome. The Irish retained their way of life through to the first Norman invasion of Ireland in 1185, when the Normans built castles in order to keep the Irish subservient. The problems arose when the Norman lords married locally and became Irish. The real catastrophe, though, came with the Reformation. The English Civil War came to Ireland with Oliver Cromwell. In his bid to further Puritan ascendancy, Cromwell had killed off half the population of Ireland. Some 100,000 Irish were enslaved and shipped off to the plantations in America. There they intermarried with black slaves which resulted in American blacks with Irish names. This fact has only come to light recently.

Meanwhile, Sir Walter Raleigh brought back potatoes from the New World, first to Cork in 1598, the first potato planting in Europe. The Irish peasants grew grain to pay their rent and the tithes owed to the Church of Ireland (Anglican), but around the edges of fields grew potatoes. With this good, cheap food, the Irish population soared. From about 600,000 left in Cromwell’s day, there were three million Irish a century later, and 6.5 million by 1801. There were 13 million by the mid-1840s Famine, caused by disease in potato crops, then the population dropped precipitously.

The Irish paid £10 passage to shipowners and provided their own food to emigrate aboard the empty timber ships returning to North America from Britain. Once here they could work on the canals in the summer and in the timber trade in the winter and soon have enough funds to settle as farmers.

In Ireland, many Presbyterians united with the Catholic Irish in opposition to the Church of Ireland. Thus they settled with the Catholics in the Ottawa Valley. The British Colonial Office saw Upper Canada as a home for loyal, Protestant families who would oppose any American aggression. Lanark was settled partly by Highlanders, all Presbyterian. In 1823 Peter Robinson brought out what were regarded as “drunken Irish rebels” from the Cork area and settled them in the Valley. There were also numbers of Anglican settlers from Tipperary.

This settlement pattern of mixed groups of Irish farmers differed greatly from the American experience, where the unskilled Irish formed the lowest orders of society in the large cities. Also, our settlement was largely completed before the desperate days of the Famine. Thomas D’Arcy McGee came to Canada in 1847, sent by the Boston Patriot, to report upon the situation of the Irish in the Canadas. He found literate Irishmen living in dwellings which one could not tell from those of other settlers. They had done better than the Irish in the United States.

Life in Canada was too hard, and the climate too cold, to carry on the old animosities from Ireland. In our stable agricultural Valley communities, one can still tell the old divisions – Curries are Protestant, Currys Catholic; Cavanaughs are Protestant, Kavanaughs Catholic – but we have arrived at a situation where a Grand Master of the Orange Lodge could become Parade Marshal for the St. Patrick’s Day parade in Douglas.

Following his presentation Terry answered numerous questions and signed copies of his book on the fire of 1870.

Presentation by Terry Currie. Article by Owen Cooke. Photos by Maureen McPhee. October, 2017.

On Wednesday, 18 October, twenty-six members and friends gathered at Pierces Corners Hall to hear Terry Currie discuss the Irish experience in the Ottawa Valley. Although Terry was born in British Columbia, he came with his family to be part of a multi-generational farming experience on the old family farm near Kinburn, without electricity and working with horses. Educated in a one-room school at Fitzroy Harbour, he went on to the more modern Arnprior High School, then to St. Patrick’s College in Ottawa where he studied History and English. After a career of high-school teaching, mostly at Almonte High School, in retirement he returned to the University of Ottawa to study history. His Master’s thesis became his first publication, The Ottawa Valley’s Great Fire of 1870. Since then he has been busy teaching and writing on various aspects of Ottawa Valley culture.