6000 Years Up the Ottawa River and Into the West

~ Report by Margot Belanger ~

Our guest speaker, Richard Van Loon, took us travelling back in time, and up the Ottawa River – a very interesting trip!

And the stars of this historic time were not French explorers like Samuel de Champlain, the courriers du bois or the Voyageurs, but the First Nations people. In Van Loon’s opinion, the Europeans’ eventual success in exploring and developing the New World would not have been possible without the First Nations’ knowledge and their willingness to give permission for foreigners to travel through their land.

Our journey began about 500 million years ago, when the Ottawa Valley was formed. The Ottawa River was much younger, only about 8,000 years old, formed after the Ice Age when huge amounts of water flowed down the valley. The discovery of First Nations artifacts on Morrison Island points to people living there for thousands of years. It was a key point for a number of major First Nations trade routes, and the artifacts included stone tools from east of the Great Lakes, and copper from west of Lake Superior.

The first means of travel were in dugout canoes, laboriously made by burning trees down, then burning and scraping out the interior of the log. Later, canoes were made of bark. Birch was the best bark, but when not available, they would use other kinds, such as elm.

Jacques Cartier was the first European to reach the Saint Lawrence River, and he attempted to establish a settlement at Hochelaga in 1535 and 1541, but he failed in his efforts.

It was Samuel de Champlain who came to Tadoussac in New France in 1603, and could be considered the true “father” of New France. Champlain was a well-educated Frenchman who had been a soldier and travelled widely; he also had a royal stipend, a privilege that many other explorers did not enjoy. He made contact with the First Nations people, whom he liked and respected. He wisely formed an alliance with the Algonquins, and fought with them against the Iroquois Confederacy, making enemies of these fierce warriors for the better part of the 17 th century.

In order to establish better communications with the First Nations, Champlain arranged what might be considered the first student exchange program! In 1610, he delegated young Etienne Brûlè to trade places with an Algonquin named Savignon, the son of Chief Iroquet, so that both men could learn each other’s language and culture. Brûlè heartily embraced the First Nations culture and travelled widely throughout their lands.

Champlain made two voyages inland, on the Ottawa River, one in 1613 and one in 1615-16. His motive was not strictly exploration; Champlain hoped to eliminate some of the middlemen that made the fur trade up the Ottawa River and beyond so expensive, and he planned to build a stronger relationship with the First Nations along the trade route, and gain their permission to travel freely without paying tributes.

Starting from Montreal in May of 1613, his travelling party soon encountered the many challenges that the Ottawa River threw at travellers, including rapids, strong eddies and thick woods that made portages miserable and dangerous. On June 4th , the party reached what today is the Ottawa-Gatineau region. Further north, they undertook a long portage inland to avoid the worst of the rapids, aiming for Muskrat Lake near present-day Cobden, through dense mosquito-infested forest. It was along this route that an astrolabe (surveying instrument) dated 1613 was discovered centuries later that may have been lost by Champlain.

From Muskrat Lake, they were able to make their way to present-day Pembroke and Tessouat Island (now called Morrison Island), so named by Champlain for the First Nations chief who controlled this strategic trading centre and extracted “tariffs” from travellers going up or down the river. Unfortunately, Champlain failed to convince Tessouat to allow him free passage farther up the river, and he decided to turn back. But he cleverly let it slip that four big ships, loaded with items for trade, were sitting down in the Saint Lawrence River, and Champlain’s homeward trek was considerable more grand than the first leg of his journey: a total of 80 native canoes loaded with furs accompanied him home!

Champlain’s second expedition of 1615-16 was more successful; he travelled to Huronia and beyond. He made excellent maps, and wrote a 5-volume series of books entitled “Voyages” that are available on-line. In these journals, Champlain referred to the First Nations people as “les sauvages”, but this was not meant as a pejorative term; he meant it to be interpreted as “people who live in the wilderness”. Champlain died in 1635 in Quebec City, but his burial site is unknown.

Perhaps Champlain’s greatest legacy was his approach to dealing with the First Nations; he did not see Europeans as conquerors, but rather traders and partners with the First Nations, and he respected their ownership of the land they occupied. The philosophy was characteristic of the approach the French took the entire time they occupied New France. Indeed, for decades, Quebec City was a very small colony, with perhaps 20 permanent residents; even by 1640, there were less than 360 full-time residents.

From the initial activities of the coureurs de bois, the fur trade grew to be a serious, very lucrative business dominated by the Voyageurs, who, unlike the coureurs de bois, did not live among the First Nations people, but worked on contract for the North West Company.

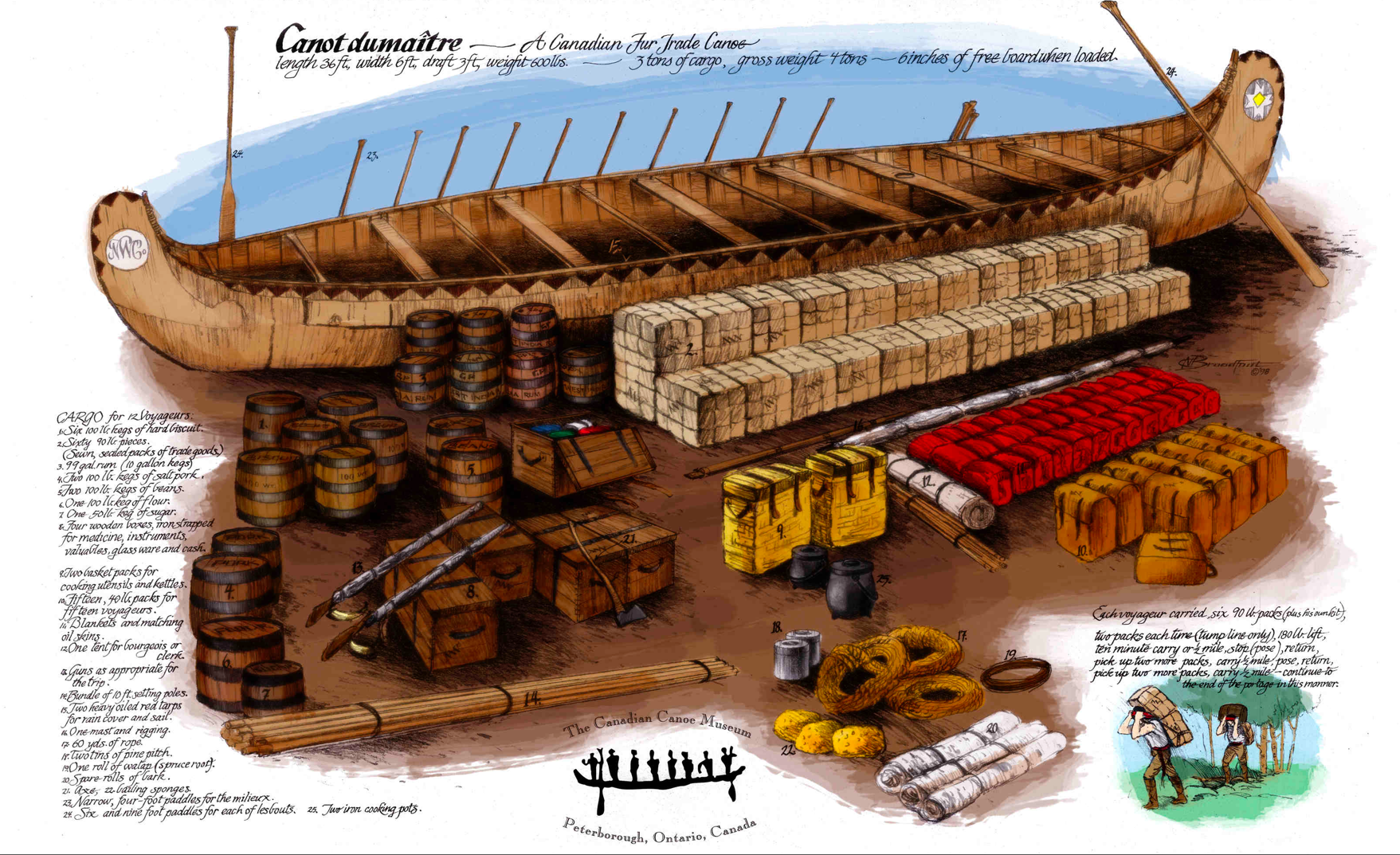

The Voyageurs were small but very strong men, who fit more easily into the legendary 40-foot Canots du Maître, which weighed 300 pounds and could carry four tons of goods and 15 people. (See illustration below.) There were 30 portages on the Ottawa River alone, and these men had to carry two or three 90-lb. packs (of supplies, furs, etc.) on these treks, as well as transport the canoes.

Convoys of up to 90 canoes would travel up and down the Ottawa River, with perhaps 1000 men. They worked 15hour days to take advantage of the longer daylight hours. It was a dangerous occupation; there are lots of crosses along the river marking hastily-dug graves. Unlike Champlain, the majority of these men were illiterate and there is no written record their adventures; perhaps they were too tired to be bothered!

As time went on, and the lumber trade started to dominate the economy of the regions surrounding the Ottawa River, the Voyageurs had to contend with the lumber drives in the river. Finally, in 1821, the North West Company merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company, and the fur trade routes centred on Hudson and James Bays.

And, with that, the Voyageurs no longer paddled the Ottawa River. An amazing era had ended.