Theodore De Pencier: The Intriguing Life & Times of the Pioneer Surveyor of Marlborough Township

In the history of Rideau Township, the name of Theodore De Pencier (1750-1824) is best known as the man who first surveyed Marlborough Township in 1791. Less well known is the intriguing life he led prior to taking up the surveying profession, and the rather desperate times he encountered in his later years.

Early Life

Christian Theodor (Braunschweig) was born the illegitimate son of Charles I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (Prussia/Germany) and a married Frenchwoman. (At the time of Theodor’s birth, the Duke already had 8 children with his wife.)

Following the death of his natural mother’s husband by suicide, his mother married a Franco-Swedish nobleman Georges-Henri de Pencier, the surname Theodore would carry for the rest of his life.

Theodore was an exceptional horseman who, at the age of 16 became the standard bearer for his military unit, and by age 21 was promoted to lieutenant, ultimately joining the 4,000 strong Hessian cavalry that would travel to Quebec in support of the British forces in North America during the American Revolution.

In 1776, under Quebec commander-in-chief in Sir Guy Carleton, De Pencier’s unit found initial success in driving the invading Americans out of the province and south into New York. However, they subsequently suffered a major defeat at Bennington NY, and were imprisoned for a time. (It has been suggested that de Pencier likely first met frontier spies Roger Stevens and Stephen Burritt at this time and place) De Pencier (by then a Captain) spent the remainder of the Revolutionary War near Sorel, Quebec.

Returning to Europe in 1783, De Pencier stayed only long enough to obtain his Honourable Discharge and British naturalization. He returned to Canada the next year, but couldn’t find work, which he attributed (in part) to his military training, which made him an exceptional swordsman and horse handler, but unsuitable as a lumberman or farmer – or businessman. Despite having been awarded a grant of 300 acres for his military service, he considered the challenges of clearing and developing the land insurmountable.

A New Career

Finally, at age 35, in desperation, and with a wife and son (Luke) to support, .De Pencier took up land surveying. In 1789 he received his full commission as a surveyor.

In 1791, after a series of survey assignments, Theodore De Pencier was commissioned by the Surveyor General in 1791 to survey the new Township of Marlborough.

As it turns out, De Pencier became one of the ablest and most conscientious surveyors in the Canadian service. Skilled in astronomy, mathematics, languages and the principles of engineering, he was possibly one of the most accomplished men in the Canada of his day.

One of the more challenging aspects of the surveyor’s job at this particular time was dealing with Loyalist settlers who had fled north after the American War of Independence and built homesteads on and around the Rideau before it was legally surveyed.

A case in point was that of Roger Stevens, who was obliged to relocate further down river when it became clear he had settled illegally. (Some accounts suggest that Stevens made his home available to De Pencier’s survey crews, but given the circumstances, that claim may be in some doubt.

Extracts from the journal of Theodore De Pencier, surveyor of Marlborough Township, 1791.

May 16 -The first concession is now surveyed. It took me 14 days from the 3rd of May to the 16th inclusive.

...I had to send my men to Mr. Stevens' house (the father of Martha Burritt) to sharpen their axes.

May 25 - A heavy rain this after- noon interrupted work for a while, and the mosquitoes and black flies tormented us furiously for the first time.

June 16 - To protect ourselves from the black flies we made a banked fire, which got out of hand during the night, and almost caused a disaster when a large tree fell directly onto us.

July 28 - The other five men, newly engaged in Montreal, were, as they left the Rideau River, already plotting to make off, since they could not endure the thirst or the burden of their loads.

September 25 - Noel Timans, the best man of the crew, was shaking with fever.....One storm followed another, and the day went on like this without anything being done. .. It is as if all the curses are let loose upon my party.

Hard Times and a Sad End

De Pencier lived in a society and time where advancement very seldom took account of merit. He was the classic outsider who the local Governor (Haldimand, at the time) had said was unemployable because he was a "foreigner".

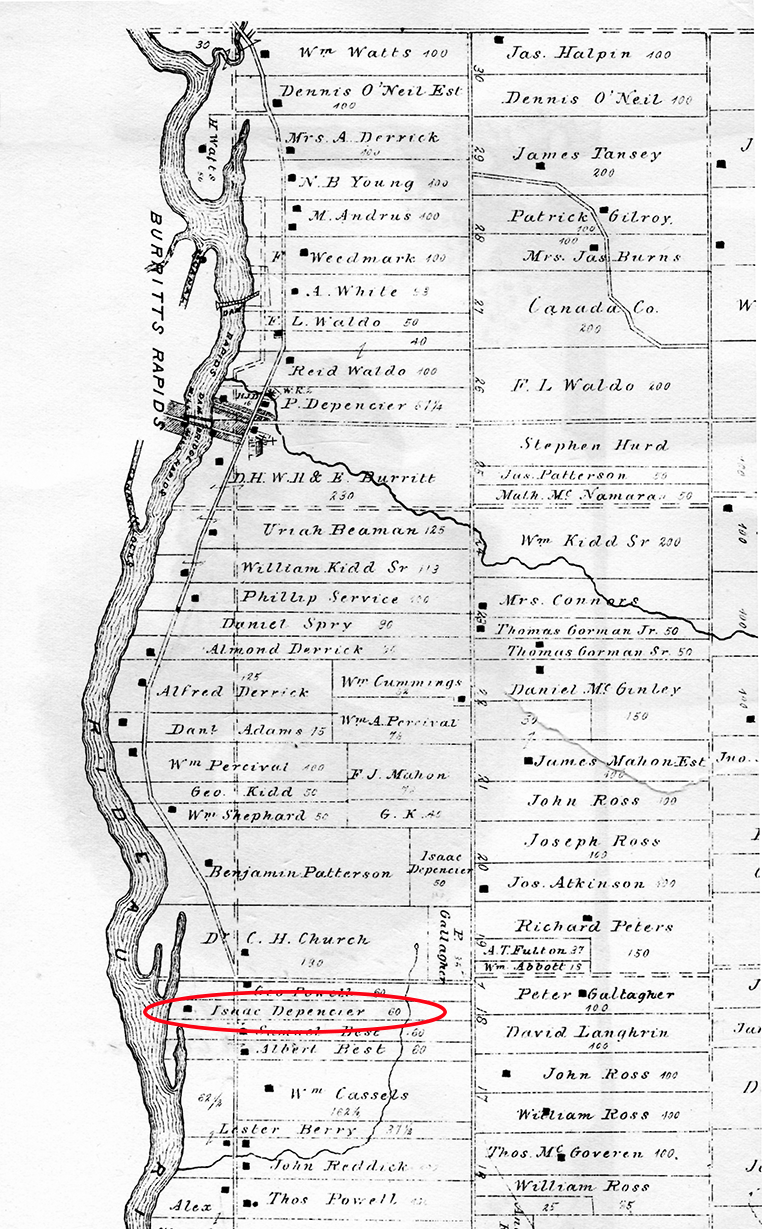

Consequently, and despite all his talents, De Pencier generally led a life of poverty. Unlike his fellow officers who served against the Americans, and his contemporaries in the Surveyor General's employ who were given grants of thousands of acres of land, De Pencier drew meagre rewards for his service. Payment for his survey of Marlborough was still outstanding in 1800, and it was not until 1818, four years before his death, that his family was awarded his small land grant in Marlborough.

In 1824, at the age of 74 Theodore De Pencier took his own life, while confined to a residence for invalid Loyalists. His remains were buried at Fort William Henry. In a final act of discourtesy, a British soldier reached into the coffin and removed the former Hessian officer’s sword.

A Generous Gift – A Lasting Legacy

While Theodore did not volunteer for active military service when war with the Americans broke out in 1812, his son Luke and daughter-in-law Gertrude did. With pride, the elder De Pencier gifted them with the Marlborough land he had marked out for himself in 1791.

Luke and Gertrude farmed Theodore’s grant, raising ten children, many of whom, along with their descendants found employment on the Rideau front. Some served as lockmasters on Colonel By’s canal, others as captains on Rideau steamers. All did so on or near lands first surveyed by the family patriarch, Captain Theodore De Pencier.

An Important Contribution

Theodor De Pencier’s significance today is that he produced a survey that knowledgeable contemporaries judge to be "much more accurate than any other", and that he was one of a handful of surveyors who opened the country beyond the St. Lawrence to settlement in the decade after the American Revolution.

And he also left a remarkable journal in which he kept a vivid account of the first loyalist settlements in Ontario and the immense difficulties with which he and his crews struggled in the conditions of spring flooding, rough terrain and the mosquito-infested swamplands of the Rideau Basin.