“Walkin'” in North Gower: A Music Phenom Passing Through

by Stuart Clarkson

On a sunny day in April 1957, a Desoto Firedome station wagon marked “Imperial Records” pulled to a stop on Highway 16 beside the Ashwood House in North Gower. Telephone operator and amateur photographer Elsie Hyland, working in the telephone exchange office next door, must have seen it stop. As someone got out of the vehicle, she quickly ran out to her own car parked across the street to grab her camera in time to snap a hurried shot – before even getting out of her car – of a bemused Antoine ‘Fats’ Domino, ready to walk up Main Street.

From the photographs, it seems Domino and crew were headed south in the late morning of Thursday 18 April, having performed at the “Biggest Show of Stars of 1957” show in Ottawa the night before. Fats was the headliner, with a line-up of performers including Chuck Berry, Clyde McPhatter, and Paul Williams Orchestra, performing 45 shows across the continent. Domino’s hit single “I’m Walking” was reaching the top of the charts, and the movie “Shake Rattle and Rock” in which he starred had just passed through Ottawa the week before, so the Ottawa crowd had been primed and ready for his arrival. Domino and the other acts did not disappoint, but Ottawa was perhaps lucky. Weeks earlier, Domino had missed several tour dates due to illness, and one of the band cars had caught fire near Washington DC.

In Ottawa, things had been tame. Out on the Auditorium floor, police had kept an eye on things and twice had had to threaten cancelling the show if the audience couldn’t stop dancing and remain seated. But there was no racial and drunken tension that newspapers claimed was fueling violence at some American venues. There had been riots at four Domino shows in 1956, with a Connecticut date being cancelled simply due to the fear of a fifth.

When the fall version of the 1957 Biggest Show of Stars (which again featured Domino and also Ottawa’s own Paul Anka, arriving in Ottawa in November) was getting ready to go on the road, it happened again – a tour stop in Washington DC was cancelled due to riot fears.

Despite these tensions, Domino saw his music making people happy, and indeed it brought them together, in some instances physically, in a way that had never happened before. At that time, some cities in the American South still forced entertainment shows to segregate their audiences, with separate afternoon and evening shows, though a few cities took their spring 1957 Biggest Show date to allow integrated audiences for the first time. Similarly, Domino and other Black musicians wouldn’t necessarily be served in all restaurants across the United States. During the fall edition of the 1957 Biggest Show, Buddy Holly famously stormed out of a place that was prepared to serve him but not the Black musicians with him. Bringing a greater consciousness of Black culture was not Domino’s chief aim in playing music, but it clearly was one of its results. Things were different in Canada, of course, but nevertheless by the time that Domino was walking up Main Street in North Gower in April 1957 and posing for Elsie Hyland there was little to no history of any presence of people of African descent in the vicinity. Unlike nearby communities like Ottawa, Hull and Perth, North Gower and Marlborough Townships remained largely uninvolved in the African diaspora until immigration from the Caribbean in the 1960s.

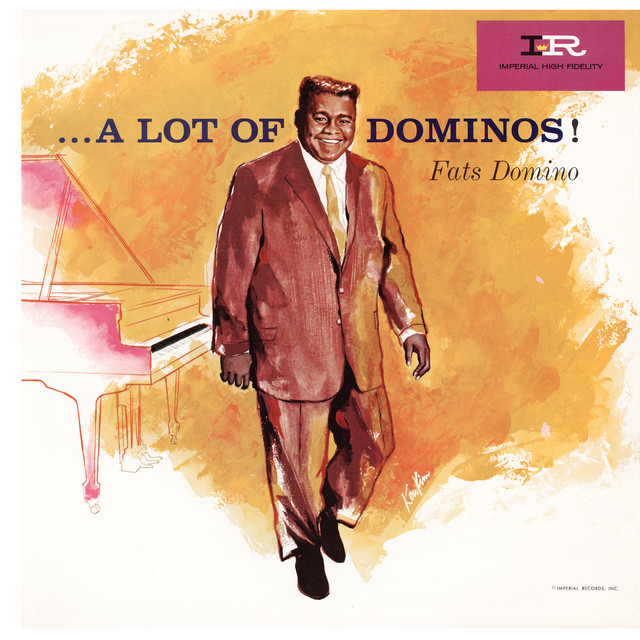

Domino's enormous popularity may have been a factor in bridging the segregation gap, yet the importance of this rock ‘n’ roll legend is perhaps not well remembered today, even if only judged in terms of his impact in the music industry. By the time of his second appearance in Ottawa that year, in November 1957 at the fall version of the Biggest Show of Stars, Fats Domino had already sold 25 million records in a career spanning less than a decade. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame credits Domino with more hit records than Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Buddy Holly combined. Domino’s music was formative for the careers of Ernest Evans (whose stage name Chubby Checker was a direct pun on Fats Domino’s name) and the Beatles, among many others, as well as influencing Jamaican artists developing ska. A prolific artist, Domino left his estate the rights to over 1000 tracks. But even in the 1950s, the real money (for musicians, at any rate) was to be made in touring, not in record sales or royalties. At the time, it has been estimated that Domino was earning the current value of $4.5 million a year playing live shows.

Ironically, Hyland’s photographs catch Domino not performing the music that he loved but on the road to the next gig, posing for a fan’s camera, which presented tougher challenges for the star. According to a 2007 Rolling Stone interview, “eating food he hasn’t cooked and talking to people he doesn’t know rank near the top of his list of least-favorite activities.” It is said that Domino stopped playing live shows because he couldn’t handle the food anymore. As a Forbes 2017 obituary article put it, “... New Orleans was the only place where he liked the food. He would take his own pots and pans on tour with him.”

Perhaps the Ashwood, or the Bide-A-Wee next door, made the cut that Thursday morning, or maybe Fats was simply grabbing a coffee before heading back out on the road.

Sources: Ottawa Journal; A Rock 'n' Roll Historian (blog); The Pop History Dig (blog); “Fats Domino Concerts: Riots and Rock N' Roll” American Masters (KET.org); Rick Coleman, “Fats Domino: Timeline of His Life, Hits and Career Highlights” American Masters (PBS.org); Charles M. Young, “Fats Domino, Big Easy Legend, Hits New York” Rolling Stone 2007; Mark Beech, “Rock Legend Fats Domino Dies At 89: A Look At His Career” Forbes 2017.